Papert’s problem of learning

How is it that learning takes place, in a most fundamental level, at least for us humans (an, presumably, for other animals as well)?

That’s obviously an important question if you are (as so many seem to be as of lately) interested in making inteligent machines - machines that are able to do more of the stuff that we are able to.

But, and this might be less obvious, it’s important for many, many other reasons as well. It is, or should be, an essential question for anyone interested in performing any work other than completely repetitive work or, put another way, anyne interested in living a “genuine life”, whathever that may be.

And that should be essentialy everybody - or so Seymour Papert argues in his Mindstorms.

That, by the way, is one of the best and worst titles I’ve come across: it hardly sounds like a serious book title; and yet, it has an appeal to a younger public that is possibly what he meant in the first place (and might explain how LEGO appropriated from it); also, it’s hard to think of a “good” title for this sort of work.

Before talking about an author’s work, I often find it useful to have an idea of their background. So, here’s a brief overview of Papert’s background:

- Papert attended the University of Witwatersrand, receiving a bachelor in arts and philosophy;

- Followed by 2 doctorates in mathematics followed by another doctorate in mathematics;

- Followed by several research positions, in many places throughout Europe;

- Importantly (for us, here) he spent some time working with Piaget, on the development of enfants;

- And then later at MIT, as, among other things, the co-director of the AI Lab, co-creator of (what would later be called) the MIT Media Lab, and professor of math and education.

That gives an idea of what he did, but also may help to ground some of what he “preached”, namely that education is a permanent process:

One shouldn’t separate education from practice

A primer on Piaget’s (and Papert’s) learning theory

Piaget studied the development of children, has written books and is most remembered for that. On that he noticed many interesting phenomena, and came with explanations for those phenomena, that came to ground what can be called a theory of learning, that is the constructivism.

Actually, Piaget can be said to take part on the broader intelectual tradition of structuralism, which some say he just renamed (or rebranded) constructivism for political reasons, but never mind that. We will talk about constructivism here.

The idea is of constructivism is pretty simple

- People have what can be called constructions on their heads;

- Those constructions can also serve as construction blocks and;

- In order to learn anything, we make use of those blocks, by combining them in different ways or what have you

Importantly, (1) learning is a process of construction and (2) one can only construct with tools previously acquired.

One I thought of that, it seemed to me a pretty reasonable, almost obvious, idea, acercely worth spelling. But from that sprout many ideas about the nature of learning, as well as what the better learning environment could be.

That is something greatly taken up by Papert1. He spend a good amount of his energy on trying to improve education conditions, and improve the idea of what a “good” educational condition is like.

In particular, he strongly argued computers can offer a great platform for learning (only not the way it’s perhaps most commonly used, to program the kids - rather, he would have the kids program the computer). For that, he (not by himself, of course) developed the LOGO programming environment, featuring a turtle, that came to become a sort of symbol for other learning platforms as well (see here why it was a really good choice). LOGO deserves a post for itself though, so we leave furthuer discussion for another time.

Back to the learning environment (with in or out the computer): Importantly, it should encourage active engagement in a community of learning, in a playful manner.

Playing is important because it’s a great way of obtaining new construction blocks, as well as finding new ways of using old ones. And playing (understood in a wider sense) in a community is a great way to motivate the creation and using said constructions.

This takes to a point to something worth stressing: the “best learning” doesn’t occur in a banking model.

Freire’s2 banking model of education

I’ve been giving only sort of a rough sketch of Papert’s (and, by extension, Piaget’s) learning ideas, trying to touch in only a few of the core ideas, but this one should be clear: learning doesn’t work like depositing packets in a bank.

Yes, I know… We all hope I can learn to draw better

Yes, I know… We all hope I can learn to draw better

That is an analogy drawn by Paulo Freire, in what he called the banking model of education, that is, regretfuly, the model of education most in use in most schools. The idea there is that learning somehow works by someone better (say, a teacher, or other adults) depositing “packets of knowledge” in the learner’s minds. In that sense, each one would be somewhat like a bank, with stores of knowledge, and the role of school would be fill those stores.

If there is one idea to take from here (be it from Papert, Piaget, Freire) is: that’s not how learning works. Which is one reason most schools are so terrible, or rather, so good in shunning people away from learning - the banking model of learning is a means for domination, not for education.

That’s not to say one can’t learn stuff from people trying to stuff them with extraneous information, it’s just that it’s not really the people trying to stuff them with extraneous information that is effecting the learning, but rather a construction process.

In order for a construction process to occur there must be in the learner’s mind previous constructs from which to build new ones and, importantly, the motivation to use those constructs so as to build new ones. And the banking model of education addresses none of those points.

Now, one could have come with the constructs from somewhere else, and could have got from somewhere else the motivation to use those “packets of knowledge” in order to build their own. In that case, it could work, but the point is that when that system works, it’s for a contingent reason.

But that system wasn’t really built[^schools] for learning. Think about it,

if someone just keeps telling you stuff that’s not really related to you, or to anything you care about, and somehow links your worth, or grades you, by how much you could take of that, does that sound like education to you? More like an education proper to slaves, it seems.

The Juggling Procedure

That was mostly about how or what education isn’t, but what about what it is? As Papert said, “one can’t talk about learning without talking about learnig about something”, and so, in a try to exemplify some ideas of a learning process, I draw on the learn to juggle example (mostly taken from a section in the forementioned Mindstorms).

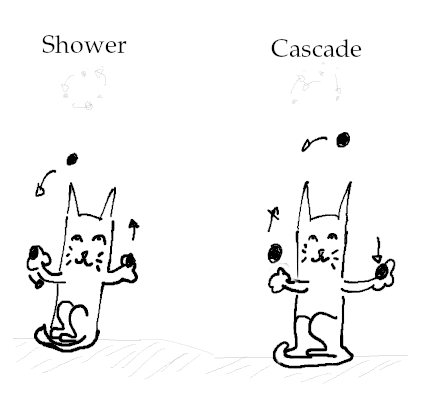

Now, there are many kinds of juggling, but we’ll be focusing in the cascade one (in constrast to, for instance, the “shower” kind of juggling)

If you’re interested in juggling and you go by that “banking model of education” briefly discussed above, you should expect to face many difficulties and to have an overall frustrating experience until you finally “get it”.

That’s because you’d see that skill as a sort of “packet” that you just don’t have, until you do. A constructivist, on the other hand, sees the learning more as a process (like “constructing”), and understands there might be different steps on the process, and thus might be better equipped to observe the process and “debug” it when something doesn’t quite work out.

That, by the way, is a reason why Papert argued computers can be so good for learning, so for acquiring new (and powerful) mental constructions:

- by programming, we build a process;

- one can more easily learn to isolate different parts of the process, and to name them (in what is usually called “procedures” or “functions” in programmign languages);

- and thus, by abstracting away details that are already understood, one literally has more pieces available to create even more complicated and interesting processes.

We can materialize that as a “people procedure” for the case of juggling.

The goal is to come up with a procedure “To-Juggle”.

As a first step, we identify and name subprocedures that might helps us achieve that goal. For us, natural candidates seem to be “Toss-Right” and “Toss-Left” (in a more real situation, just what might be those subprocedures might not be straightforward, but we’re streamlining things a bit for the purpose of this post).

Toss-Left is a command to throw a ball from the right hand and catch it with the left hand, and Toss-Right a command to throw a ball with the left and catch with the right hand.

Tossing balls from one hand to another is simple enough that most people can do with little practice, so we can concentrate in how to combine those procedures to get To-Juggle.

Timing here is essential, and the procedures for tossing balls are to be performedd in parallel, rather then serially one after the other. To deal with that parallelism, one comes with the concept of “When” - what Papert calls “When Demon”, and in computer parlance could be called “When Daemon”. The “Demon” or “Deamon” is to stand for something that is usually “sleeping”, or just not-acting, until some conditions are satisfied, and they do something. Many things could be modelled with those “When Daemons”, like, “When hungry, eat” and so on.

For To-Juggle we’ll use two When Daemons, namely When something Toss-Left” and *When something Toss-Right”, where “something*” stands for some condition we’ll have to fill in.

These conditions we’ll call “Top-Right” and “Top-Left”. Top left, stands for the following state (and Top Right for the analogous one)

With that, we get our full procedure:

1

2

3

To Keep Juggling

When Top-Right Toss-Right

When Top-Left Toss-Left

Using the Juggling Procedure as a learning tool

How can we the above procedure as a tool for learning? Having identified a seemingly suitable procedure, the following natural step is trying to apply it, and then debugging when it doesn’t work.

For that purpose, we might want a more granular procedure. For instance, we want to first be sure that the person can toss just 1 ball from one hand to another.

Then, we’ll want to be sure that she can combine 2 tosses, so to cross 2 balls from both hands. That might not work immediately. One common “bug” in the procedure is that people are used to following the balls with the eyes when tossing, which besides being confusing when there are 2 or more balls involved, makes it hard to discern the Top-Right and Top-Left conditions.

In order to “debug” that, one comes back to tossing just 1 ball, and making sure one doesn’t follow it with the eyes, focusing just in the point at the top of the trajectory instead. That is usually not difficult and most people don’t have a problem with that after identifying the behavior.

Now, before going on, just a brief note about this “debugging” we’re doing. The term “bug” might have too much of a heavy baggage, and be associated with overall bad feelings, but in our setting we still use the term, for lack of a better one, but we strip it of it’s weight. The thing is people are generally conditioned to label their actions as “right” or “wrong”, “good” or “bad”, but here we find it silly to come with an arbitrary criterion of “good” or “bad” and, instead, by seeing learning as a process, we understand that it can go on and perfect itself. And this is arguably the most important type of learning, namely learning of learning, so debugging isn’t here to “turn something bad into something good” (although it might do that as well), but rather as an instance of the learning to learn process.

After one can cross 2 balls, a third may be introduced. Some more debugging might be needed, but by following the procedure outlined above, you shouldn’t take too long before being able to be juggling around :)

Note that if instead one would follow a “brute force” approach, just getting three balls and trying to juggle them, it would probably take much longer. Not only that, but one would probably learn much less in the process - eventually, one would get it, but it would be much harder to make any debugging.

As Papert says,

People are capable of learning like rats in mazes. But the process is slow and primitive. We can learn much more and more quickly by taking concious control of our learning process, articulating and analyzing our behavior.

If you don’t quite have the balls to do it, you could try with lemons ;) - just keep in mind they rot much quicker after knocking a few times.

If you’re interested in juggling, you might be interested in this piece on A Computational View of the Skill of Juggling.

If you’re interested in learning, I’ll be writing more about it around here, so feel free to come back ^^